So right off the bat I see “lineaments” and “nascent” in the first line. I think to myself, Okay, Steve, are you sure you want to fire them there big guns? And both in one sentence? Cuz the noise they make might drown out the other words there. And do you really want to send a percentage of your readers running for a dictionary? But “lineaments” is exactly the word that fits here. “Features” is too general, too imprecise, which is a shame because a two-syllable word there would maintain a better rhythm. (Listen to the beats: “She nodded at the blah-blah of this nascent shrine.”) Same with “details.” “Characteristics” would pretty much own the entire sentence and turn any semblance of rhythm into something that sounds like sneakers in a dryer.

I like “nascent” because it’s a two-syllable word that fits the meter and says just what I want it to say. “New” would be ugly — a one-syllable word here would sound like when you’re going down a flight of stairs and you expect one more step but there isn’t one. “She nodded at the lineaments of this blah shrine.” Whump! And it would create a possible implication that there’s another, older shrine, which there ain’t. What I’m going for here is “She blah-blah at the blah-blah of this blah-blah shrine.”

By now it ought to be apparent that the sound and meter of the words together are as important to me as what they mean or how concise they are. In Steve’s world, good writing sounds good. And I may as well just say it: In Steve’s world, sometimes how it sounds is more important than what it means.

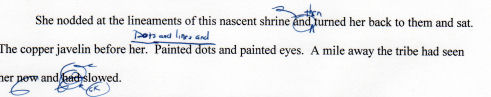

Okay, so let’s look at the actual markings on that sentence. The stet version (that is, the version prior to marked correction) basically tells you “she nodded at this and turned her back.” But that’s an implication of simultaneity, like “He walked and chewed gum.” Whereas what I’m really trying to say is that she nodded, then subsequently turned her back. I have arguments with myself about ways to go about this. I could write what I just told you: “She nodded, then subsequently turned her back.” If your view of fiction writing is that it’s basically a list of events, then that line is perfectly serviceable. In my view, if that’s your view of fiction, then you should write Ikea assembly instructions. Because however precise and concise it may be, it’s also ugly as hell. A turd in a punch bowl. I don’t want anything to do with it.

But once your criteria go beyond the utilitarian, the merely descriptive, you start having to make decisions. My choices here are basically “she nodded and then turned,” “she nodded, then turned,” and “she nodded, and then turned.” In my corrections I picked none of the above, opting for dropping both comma and “and”: “she nodded then turned.” I know why I did it: The elimination of a comma and the word “and” gives the sentence a much nicer rhythm and flow. I also know that I’ve changed the correction on a subsequent revision because of the likelihood of the reader tripping on the word “then” without a helpful comma or “and then.” But what I won’t do here is put in a comma followed by “and” even if it’s grammatically correct to do so. Because it fucks up the way the sentence flows.

I’ll talk in a later post about why I drop a lot of punctuation. This post is already much longer than I’d intended.

Okay, so: “The copper javelin before her.” I like the meter and I like the fragment. I use a lot of sentence fragments. Once again not grammatically correct. Once again I don’t give a shit. My loyalty is to the line itself.

Next sentence is also a fragment: “Painted dots and painted eyes.” I like the rhythm and I don’t mind the repetition of the word “painted.” Sure, taking the second occurrence out is more concise. It also takes all the air out of the sentence, and makes it unclear whether the eyes are in fact painted as well.

Above “Painted dots” I’ve drawn a line, and above the line is written “Dots and lines and”. This is my way of indicating an alternative. I’m leaving a note to myself that I might want the sentence to read “Dots and lines and painted eyes.” I can’t decide right now, but when I go to enter these changes into the computer, the decision is almost always clear to me. Sometimes you need some distance.

Okay, last sentence [insert thunderous applause]: “A mile away the tribe had seen her now and had slowed.” Good god what a clumsy clunky sentence. That “now” just sits there like a fart in church, don’t it? So I cut it. I also cut the “had” but then changed my mind, both for the rhythm and the parallel construction. (I write “ok” instead of “stet” cuz it doesn’t take as long.)

So we started with this:

She nodded at the lineaments of this nascent shrine and turned her back to them and sat. The copper javelin before her. Painted dots and painted eyes. A mile away the tribe had seen her now and had slowed.

And ended with this:

She nodded at the lineaments of this nascent shrine then turned her back to them and sat. The copper javelin before her. Dots and lines and painted eyes. A mile away the tribe had seen her and had slowed.

Maybe the changes don’t seem like big improvements, or worth all this verbiage. But I think (or at least I hope) that if you read them out loud, you can hear the difference. (I’ll cheat and tell you that I reinstated a comma after “shrine” on the next pass.)

I’m sure I’ll get comments saying, I liked the first way better, or Why don’t you say it this way? I would like to pre-empt these by saying that my point is not to crowdsource my work but to try to present a kind of cross-section of the decisions I make in the revision process that contribute to an individual sense of style.