The handwritten —-| symbol before “Their” is my way of saying “no break” — that is, join this up with the |—- symbol that ends the previous paragraph. It’s useful when you’re cutting stuff and joining sections.

The handwritten —-| symbol before “Their” is my way of saying “no break” — that is, join this up with the |—- symbol that ends the previous paragraph. It’s useful when you’re cutting stuff and joining sections.

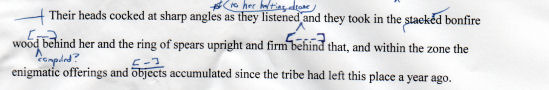

I added “to her halting drone” after “listened” to provide more concrete detail and accentuate the rhythm. I deleted “stacked” as redundant and am asking myself if I want to add “compiled” after “wood.” This would make the portion go from “and they took in the stacked bonfire wood behind her” to “and they took in the bonfire wood compiled behind her.” I see why I want the change — it just plain sounds better. I also see why I bracketed the insertion at “compiled.” I’m telling myself I want a word here but I’m not crazy about “compiled,” probably because it doesn’t feel as accurate as I’d like, and also because that “c” really sticks out. But definitely a two-syllable word belongs there.

I indicate that I want a three-syllable word — [_ _ _] — to replace “behind.” The reason is clearer if you say it out loud (I’ll replace it with in back of as a placeholder for now): “upright and firm behind that” vs. “upright and firm in back of that.”

For the same reason I also want to replace “objects” with a one-syllable word — [_]: “enigmatic offerings and objects accumulated” vs. “enigmatic objects and stuff accumulated” (with “stuff” as a placeholder).

I suppose there are grounds for saying I’m more obsessed with rhythm than is necessary for prose. But all language has some built-in musicality, different no doubt for each. I only speak English, but I always find in it an underlying musicality that I want to make more overt. It happens to me when I speak sometimes but much more often when I write. The rhythm owns the line. I’ve wondered sometimes if this is because I’m not a terribly fast reader. I don’t just see the information on the page the way you need to if you want to haulass through it. I hear the words in my head, sound them out.

I can play devil’s advocate and make the case that, since writing is communication, if the rhythm takes precedence to the extent that meaning is lost or obscured, the communication has failed. And that’s absolutely true if you think of the words as printed symbols and not as sounds. But music is communication. And I think I’m imparting information through the use of rhythm in a musical sense. Even more, I think that, unlike the printed word, such communication isn’t received in a terribly rational, forebrain way, but in a deeper, more emotional way. Somewhere beneath articulation. And that’s okay with me, because in the arts, words themselves — stripped of inflection, nuance, facial expression, tone, the support of any other medium — are rational vessels often laboring to convey emotional cargo.

Music mostly works the other way around: it goes straight to the heart without the intervention of the brain (if you’ll pardon the metaphors; it’s all happening in the brain, of course). The exception to this is jazz, notoriously the most cerebral of musical forms. Given how I am reconstructing language conventions for my own purposes you’d think I’d love jazz, but mostly I don’t. I appreciate it but I don’t like it. But I’ll definitely be using some jazz metaphors as I talk about the differences between ignoring rules, adhering to rules, and breaking the rules. Jazz is, if I may be glib here, music for musicians. It’s about messing with the pocket, the timing, not just playing the groove but playing with the groove, with the idea of groove.

Fiction can’t help but live in its head. I want it to listen to its heart too, but without resorting to the tawdry tricks of cheap sentimentality that often demonstrate how cheaply audiences are willing to be bought.

This is all starting to seem a bit of a manifesto, which was never my intent. And for all I know I’m not making a lick of sense anymore. But lately something in me feels compelled to demonstrate there is some kind of madness to my method. Believe me when I tell you I don’t sit back and marvel at my intent. I don’t want to put technique at the forefront of feeling or meaning (and that’s why I don’t like a lot of jazz). What I marvel at is that all of this happens automatically, seemingly without volition. I suppose it’s just the often-accessed and -trained series of muscles and sequences and reactions that an Olympic high-diver develops over countless hours of training and brings to bear in five seconds of beautifully configured descent. She doesn’t think about anything once she leaves the platform. She reacts. Her body does it.

The marvel for me, I guess, is how much can be internalized, rendered to a process I call neural grooving. And how much of that can be so abstract as the kind of things I’ve been talking about.