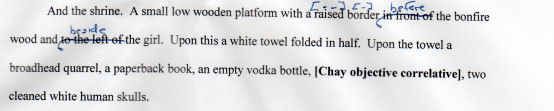

Here I don’t just start a line with a sentence fragment beginning with “and,” I start a whole paragraph with it. Again, not something I would want to do regularly, but here I think I get away with it because of the momentum of the previous paragraph, which is a single sentence delineating the features of the characters’ immediate surroundings.

Here I don’t just start a line with a sentence fragment beginning with “and,” I start a whole paragraph with it. Again, not something I would want to do regularly, but here I think I get away with it because of the momentum of the previous paragraph, which is a single sentence delineating the features of the characters’ immediate surroundings.

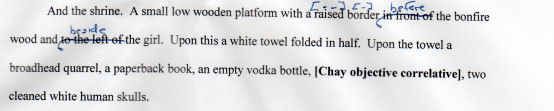

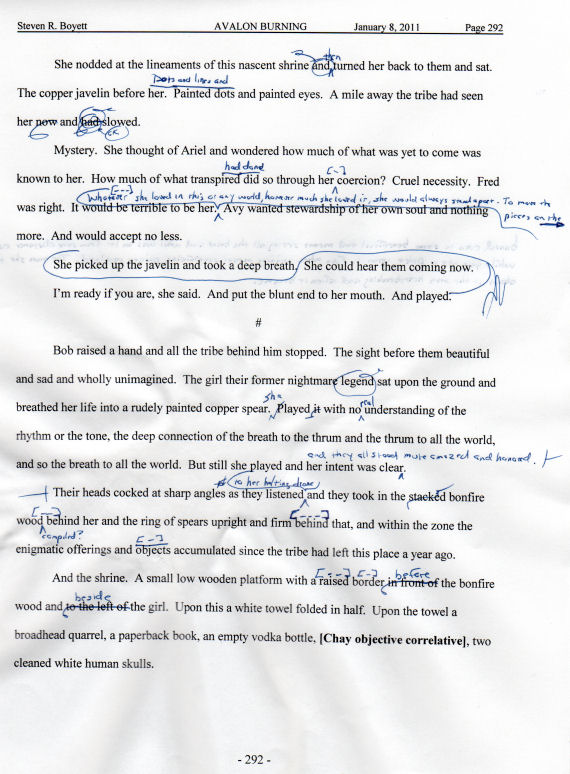

The next line is the only one here with actual marked corrections. I want to replace “raised border” with a two-syllable word followed by a one-syllable word, so that the rhythm changes from “A small low wooden platform with a raised border” to “A small low wooden platform with a blah-blah blah. The meter of that sentence just sounds better to me, and I will do some searching to find the two words I want there.

Sometimes I ignore these suggestions to myself, either because the words that are there are exactly the right words regardless of their meter, or because I realize I am sacrificing clarity or precision for the sake of meter. But sometimes that sacrifice is okay. It’s a judgement call — as is every word and punctuation mark in the entire book. For instance, that second sentence omits a comma between “low” and “wooden,” entirely because in this case I don’t want to sacrifice the meter of the sentence to the pause the comma would interject. Here the comma’s absence doesn’t make the sentence ambiguous or confusing. Its addition would be entirely for the sake of form, and I’m happy to dispense with form if it interferes with my intent. Omitting the comma isn’t a rule, either — I’m happy to use the comma if I like what it does to the sentence. Again, my loyalty is to the line, the image, the flow, and not to some sense of propriety for its own sake.

Finally (yay!), I’ve embedded a note to myself in the manuscript, bracketed and bolded. When I revise the entire manuscript I do a search for brackets to be sure I haven’t missed any of these. It’s easier to do than you think. A friend of mine told me about a book he read that somehow got one of these printed — it slipped past the author, editor, copy editor, and proofreader — where a character in the Navy was described as serving on the [INSERT BATTLESHIP NAME HERE]. This thought gives me the straight-up willies. Talk about showing up in your underwear.

For me this is about the most naked moment in this whole series on revision, because it doesn’t just show some things about my process and how I go about establishing or reinforcing elements of style. It shows how sometimes the most gut-wrenching, emotion-laden, and even linchpin images and incidents in a book can be mostly unknown to the author during the entire process of creation. The author knows he wants something here. He knows its significance and he knows how he wants to establish it, reinforce it, and pay it off later. He trusts his instincts. But what he doesn’t know is what that thing is. So he makes a placeholder. Imagine Tolkien chewing on the end of his pencil and thinking, Should it be a bracelet? A music box? A paperweight? ‘The Lord of the Paperweights.’ Hmm. I better just bracket this and come back to it.

So the note here says Chay objective correlative. “Chay” is a character in the novel. “Objective correlative” is a term coined by T. S. Eliot to describe the emotional associations an object can acquire through its context in a dramatic form. The lazy cliche objective correlative used in movies is a music box: Guy gives girl a music box at some point. Later guy is dead and girl finds music box and weeps as it plays. This objective correlative is so hackneyed in Hollywood that the moment someone in a movie gives someone else a music box, he might as well paint a bullseye on his forehead.

In Avalon Burning I have a moment where Chay’s uncle undergoes a ritual death, and he bequeaths several things to Chay, whom he has mentored since the death of Chay’s parents. Among these is an object that I want to evoke a sense of the relationship between them. I want it to have a sense of history and imply that it might have been hard-won. And I want it to be something that vividly conjures that uncle and that association and all those years of learning and struggle and companionship whenever the object resurfaces.

To do this you have to introduce the object properly — it must be revealed in circumstances that are emotionally charged, and it must clearly imply its history without exposition, and especially without cheap sentiment. It must be subsequently reinforced at least once, to provide a throughline in the narrative, and usually in a context that is not emotionally charged, but often more introspective or casual. And finally it must be reintroduced in a way that laminates our associations with Chay and his feelings toward it with our previous associations of how it was originally received and what it originally meant.

In a way it doesn’t matter what the object is. It could be a knife, a bracelet, the last Godiva chocolate bar in the world. The meaning isn’t in the thing itself but in the way we associate it with its circumstance and history. The important thing is to avoid the obvious and cliche, and to carefully pick something that implies an interesting history and isn’t at odds with the role you want it to play. (I hope it is clear here that I am not talking about a “McGuffin,” which is an object that propels a plot [the Maltese Falcon, the Chevy Malibu in Repo Man], and not an object intended to evoke certain emotions through association with events we have witnessed.)

The power of the objective correlative is in our brain’s ability to abstract. “Abstraction” may be defined as “the ability to consider a thing apart from itself.” We are able to abstract to the extent that we actually confuse a symbol for the thing it symbolizes, even in direct contravention of the original thing. Think about the paradoxical irony of passing laws against flag burning. A flag is a piece of cloth. Burning it does nothing to your country. Burning an American flag manufactured in China would be comical without the emotional associations with which the flag is imbued. But passing a law to prevent the burning of an American flag (manufactured in China) essentially contravenes a fundamental law of the country the flag symbolizes (freedom of expression).

All of this litigation and emotion and controversy exists entirely because of our ability to abstract. To make virtually anything into a symbol. Artists take advantage of this by working carefully to lend a sense of meaning to chosen objects. This is the bread and butter of a propagandist (and there’s a case to be made that artists are propagandists, in that they are using media to manipulate audiences toward some goal).

In the case I’ve noted on the page I’m very publicly revising, I simply want something that will add a solid emotional line and payoff in the book, a tangible way to concretely represent some emotional situations without resorting to exposition (which would carry no emotional weight at all) or forced sentimentality (which is so cheaply laden with lazy adjectival manipulation that it is off-putting [though, unfortunately it also seems to work for a lot of audiences]). I simply don’t yet know what that object is. But I will. The book itself will tell me.

There is a lot of power in the notion that you can turn a dinner fork into something that can make an audience gasp, or cry, or mourn, when it is produced. If you do it right.

The reading and subsequent interview at Capitola Book Cafe on Saturday went very well, though there was some danger of there being more participants than attendees.

The reading and subsequent interview at Capitola Book Cafe on Saturday went very well, though there was some danger of there being more participants than attendees. I consolidated the audio I have posted here and on my

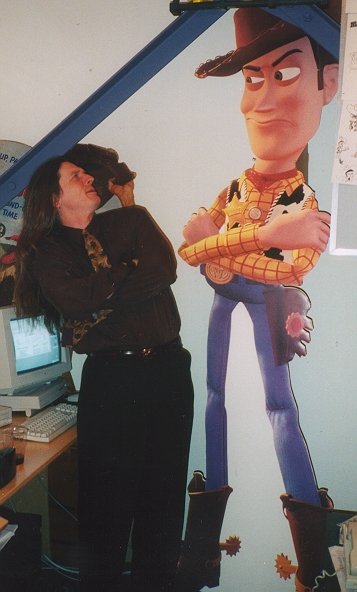

I consolidated the audio I have posted here and on my  I was writing the second go-round of Toy Story 2 at Pixar. This was when they were in Point Richmond, before they moved to a much larger facility in Emeryville.

I was writing the second go-round of Toy Story 2 at Pixar. This was when they were in Point Richmond, before they moved to a much larger facility in Emeryville.

The

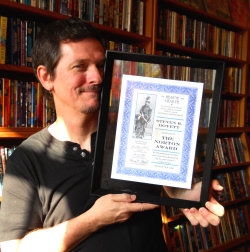

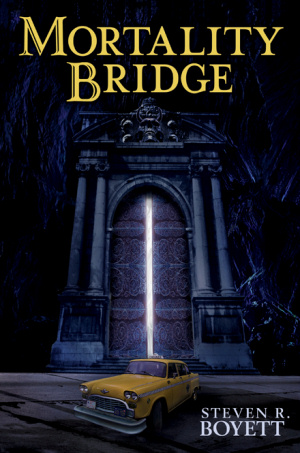

The  I just learned that the signed, limited hardcover edition of Mortality Bridge has sold out at Subterranean Press. Thanks so much to everyone who bought one.

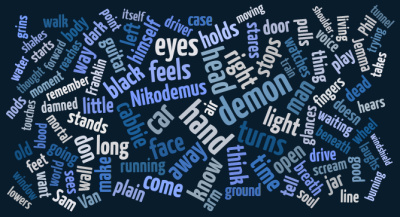

I just learned that the signed, limited hardcover edition of Mortality Bridge has sold out at Subterranean Press. Thanks so much to everyone who bought one. A “word cloud,” in case ya don’t know, is a visualization of the most frequently used words in a given text. The total number of words are analyzed and then the most common ones are moved to the top of the list. A graphic is created that weights the words by size and color to demonstrate how often they occur.

A “word cloud,” in case ya don’t know, is a visualization of the most frequently used words in a given text. The total number of words are analyzed and then the most common ones are moved to the top of the list. A graphic is created that weights the words by size and color to demonstrate how often they occur.

In Conjunction with the previously issued

In Conjunction with the previously issued

I have not & will not open a Facebook account because I take serious issue with that company’s privacy (or lack thereof) policies, and I basically feel that a fundamental disrespect of and disregard for their user base is ingrained in the company’s DNA. I’m sure that for many users — indeed, for most users — Facebook is helpful, useful, and valuable. That doesn’t mean it ain’t evil.

I have not & will not open a Facebook account because I take serious issue with that company’s privacy (or lack thereof) policies, and I basically feel that a fundamental disrespect of and disregard for their user base is ingrained in the company’s DNA. I’m sure that for many users — indeed, for most users — Facebook is helpful, useful, and valuable. That doesn’t mean it ain’t evil. I have released

I have released  The audio recording of “Chapter 2: Crossroad Blues” from Mortality Bridge is

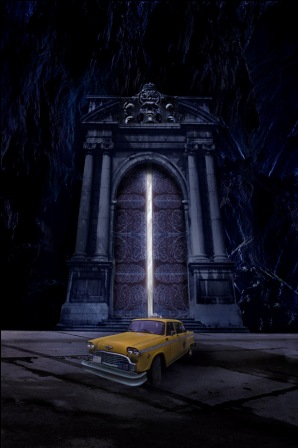

The audio recording of “Chapter 2: Crossroad Blues” from Mortality Bridge is  The Mortality Bridge

The Mortality Bridge

o now whenever someone asks me, “What’ s the best meal you’ve ever had,” I get to say, “A can of Spaghetti-O’s and a vanilla pudding pack.”

o now whenever someone asks me, “What’ s the best meal you’ve ever had,” I get to say, “A can of Spaghetti-O’s and a vanilla pudding pack.”

I wonder if “camera shy” is an anachronism. It’s hard to imagine anyone under thirty being camera shy. A generation born with the camcorder and raised on increasing megapixels and direct-digital recording to the extent that pictures and videos are routinely recorded by telephones (!) and placed on a global bulletin board, a generation whose fawning and narcissistic Baby Boomer parents insisted on recording every diaper change and Gerber’s yark before handing that torch off to the kid’s own grasping hand — camera shy? Yehright.

I wonder if “camera shy” is an anachronism. It’s hard to imagine anyone under thirty being camera shy. A generation born with the camcorder and raised on increasing megapixels and direct-digital recording to the extent that pictures and videos are routinely recorded by telephones (!) and placed on a global bulletin board, a generation whose fawning and narcissistic Baby Boomer parents insisted on recording every diaper change and Gerber’s yark before handing that torch off to the kid’s own grasping hand — camera shy? Yehright.

Sometimes I talk in my sleep. That means that a part of me is conversing while the thinking part of me — the part I usually think of as me (during the day, anyhow) — is unconscious. I find this a bit creepy. It’s like being possessed, or operated by remote control, or having multiple personalities, or something.

Sometimes I talk in my sleep. That means that a part of me is conversing while the thinking part of me — the part I usually think of as me (during the day, anyhow) — is unconscious. I find this a bit creepy. It’s like being possessed, or operated by remote control, or having multiple personalities, or something.

Saturday night’s reading at FogCon went wonderfully, and thanks so much to everyone who attended.

Saturday night’s reading at FogCon went wonderfully, and thanks so much to everyone who attended.

Just found out Subterranean Press has a

Just found out Subterranean Press has a  Here I don’t just start a line with a sentence fragment beginning with “and,” I start a whole paragraph with it. Again, not something I would want to do regularly, but here I think I get away with it because of the momentum of the previous paragraph, which is a single sentence delineating the features of the characters’ immediate surroundings.

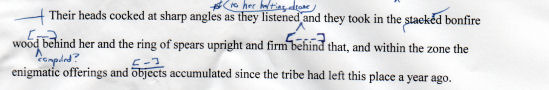

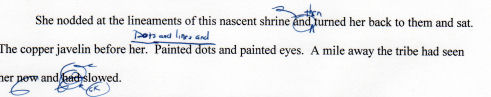

Here I don’t just start a line with a sentence fragment beginning with “and,” I start a whole paragraph with it. Again, not something I would want to do regularly, but here I think I get away with it because of the momentum of the previous paragraph, which is a single sentence delineating the features of the characters’ immediate surroundings. The handwritten —-| symbol before “Their” is my way of saying “no break” — that is, join this up with the |—- symbol that ends the previous paragraph. It’s useful when you’re cutting stuff and joining sections.

The handwritten —-| symbol before “Their” is my way of saying “no break” — that is, join this up with the |—- symbol that ends the previous paragraph. It’s useful when you’re cutting stuff and joining sections.

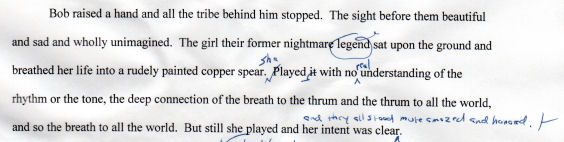

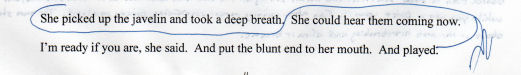

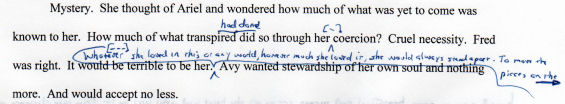

Here I’ve simply transposed the two sentences because the order makes better sense: She hears them coming and it spurs her to action. Now the sentences have momentum, whereas before the correction they were just a series of details.

Here I’ve simply transposed the two sentences because the order makes better sense: She hears them coming and it spurs her to action. Now the sentences have momentum, whereas before the correction they were just a series of details.

This is a piece of coal from the Titanic‘s debris field. Around 1994 a company called RMS Titanic, Inc., took out an ad soliciting pre-orders of these, claiming they would use the revenue to fund a scientific expedition to Titanic, and claimed the ship itself would not be disturbed. Then they promptly used the money to obtain sole salvage rights and sell berths on a cruise ship that sailed to the site, where passengers witnessed another ship the company had hired make a total botch of trying to raise a massive section of the hull, which promptly broke loose and planed back down far from where it had originally been.

This is a piece of coal from the Titanic‘s debris field. Around 1994 a company called RMS Titanic, Inc., took out an ad soliciting pre-orders of these, claiming they would use the revenue to fund a scientific expedition to Titanic, and claimed the ship itself would not be disturbed. Then they promptly used the money to obtain sole salvage rights and sell berths on a cruise ship that sailed to the site, where passengers witnessed another ship the company had hired make a total botch of trying to raise a massive section of the hull, which promptly broke loose and planed back down far from where it had originally been. This is a piece of trinitite. That’s the name given to the desert sand that was fused into glass by the heat from Trinity, the world’s first nuclear detonation, in White Sands, New Mexico, in July 1945. So yes, I own an artifact produced by the first atomic explosion. And no, I am not going to tell you where I got it, except to say that I did not buy it.

This is a piece of trinitite. That’s the name given to the desert sand that was fused into glass by the heat from Trinity, the world’s first nuclear detonation, in White Sands, New Mexico, in July 1945. So yes, I own an artifact produced by the first atomic explosion. And no, I am not going to tell you where I got it, except to say that I did not buy it. This is the

This is the  This is a fragment of the Zagami meteorite,a 40-pound hunk of rock that fell from the sky and into a cornfield in Zagami, Nigeria, in 1962. What makes it unusual is where it’s from.

This is a fragment of the Zagami meteorite,a 40-pound hunk of rock that fell from the sky and into a cornfield in Zagami, Nigeria, in 1962. What makes it unusual is where it’s from. Yeah, I know, this looks like the last picture. It’s a fragment of lunar tektite, a little sliver cut from a piece of impact ejecta that probably landed in Antarctica. Or, to make it simpler (and much more cool-sounding): I own a piece of the moon.

Yeah, I know, this looks like the last picture. It’s a fragment of lunar tektite, a little sliver cut from a piece of impact ejecta that probably landed in Antarctica. Or, to make it simpler (and much more cool-sounding): I own a piece of the moon. The signature pages for the limited edition of

The signature pages for the limited edition of